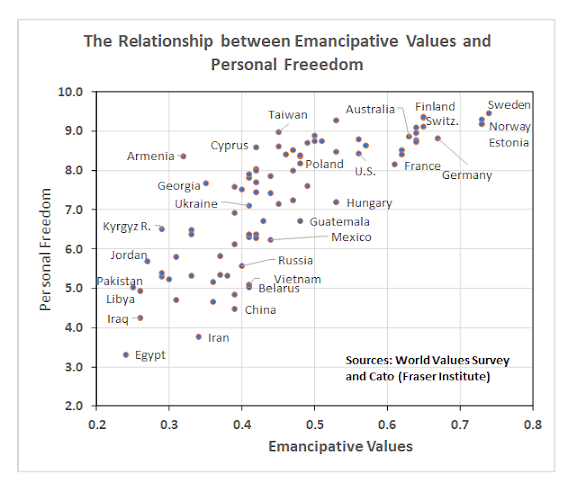

An obvious answer to the question posed above is that governments determine how much liberty people enjoy. But that response may be too glib. Some argue that much restriction of liberty reflects prevailing values of people who see individual autonomy and personal choice as a threat to collective interests of groups and nations.

When I

began the research which led to this article, I sought to explore the extent to

which international differences in personal and economic freedom can be

explained by deep-seated cultural values. My conclusion is that there is a

large residual variation which is attributable to ideologies of governments

that support or oppose free markets and personal liberty.

This

conclusion is illustrated in the graph shown above. However, you will need more

information about how the graph was constructed before you can get the picture.

- The graph shows the levels of economic and personal freedom for 85 countries using the Fraser Institute’s latest data (for 2020). There are 165 jurisdictions covered by the Fraser indexes, but relevant data on values from the latest round (2017-22) of the World Values Survey (WVS) was only available for 85.

- The vertical axis of the graph is in reverse

order – low values of personal freedom at the top, high values at the bottom. The reason stems from use of personal political compass data which is constructed

in that way in an earlier article on this blog.

- The horizontal and vertical axes are positioned at the median levels of economic and personal freedom for the 165 jurisdictions covered by the Fraser indexes. The countries not covered by the WVS tend to have lower freedom ratings than those which are covered. The median ratings for the 85 countries represented in the graph is 7.2 for economic freedom and 7.6 for personal freedom.

- I have only labelled data points that have freedom ratings that are substantially different from predictions based on deep-seated cultural values. The methods used to obtain predicted values for personal and economic freedom were explained in preceding articles on this blog (here and here). If you live in a high-income liberal democracy, that country is likely to be represented by one of the unlabelled points in the south-east quadrant - with relatively high levels of economic and personal freedom.

- The colour of the labelled points depends on whether freedom is greater than or less

than predicted on the basis of values – green if greater than predicted, red if

less than predicted. The size of the labelled points is larger if both personal

and economic freedom are greater than or less than predicted.

The graph

also shows that a substantial number of countries with relatively high personal

and economic freedom are performing better in that regard than can readily be

explained on the basis of prevailing values.

More

detailed information for the countries which have freedom ratings substantially

different from predicted levels is shown in the graph below.

Of the 34

countries with freedom ratings that are substantially different from predicted

levels, Argentina is the only one to have one category of freedom greater than

expected and the other category of freedom less than expected.

Questions

to ponder

Are relatively high levels of human freedom less secure

in countries in which freedom is greater than prevailing values seem to support?

If a high proportion of the population feels that existing policy regimes are not

aligned with their personal values, these regimes could be expected to be

fragile, other things being equal. However, much depends on those “other things”.

The growth of economic opportunities could be expected to be greater in the

presence of relatively high levels of economic freedom. That could be expected

to foster values that support economic freedom. The growth of economic

opportunities also tends to encourage development of emancipative values which

support personal freedom.

Are relatively low levels of human freedom less likely to

persist where prevailing values support greater freedom? Again, policy

regimes giving rise to such outcomes could be expected to be fragile, other

things being equal. Unfortunately, however, the “other things” often include

use of coercion to suppress opposition to existing policy regimes.

Postscript: 16 June, 2023

I have now made an effort to explore whether some of the above speculations have empirical support. This involved repeating the exercise of obtaining predictions of personal freedom - using WVS data from the 2010-14 to obtain predictions of personal freedom for 2012. It was possible to obtain matching data for only 53 countries.

There is some evidence that personal freedom is less secure in countries in which freedom is greater than prevailing values seem to support. Of the 6 countries in which personal freedom was much greater than predicted in 2012, only one had higher personal freedom in 2020, another had unchanged personal freedom and the other 4 had lower personal freedom.

The exercise

provided no support for the proposition that relatively low levels of personal

freedom are less likely to persist when prevailing values support greater

freedom. Of the 6 countries in which personal freedom was much less than

predicted, none had higher personal freedom in 2020, and 2 experienced a

further decline in personal freedom. Unfortunately, over this period none of the repressive regimes were displaced or became more responsive to prevailing values of the people.