Spencer went

on to suggest that trade would have been more successful in the absence of the

privileges that the British government had conferred on the East India Company

(EIC):

“Insane

longing for empire would never have burdened the Company with the enormous debt

which at present paralyzes it. The energy that has been expended in aggressive

wars would have been employed in developing the resources of the country.

Unenervated by monopolies, trade would have been much more successful.”

Prior to my

recent visit to India I was aware that classical liberals like Herbert Spencer

were critical of the East India Company. Since my visit I have become an expert

on all matters pertaining to Indian history. Just joking!

I can only claim

to be able to sketch the outlines of the story of how the EIC ended up ruling

India. I think the story is worth telling as a case study of the unintended

consequences of government intervention in international trade.

Spencer was

correct in identifying the importance of the EIC’s links to the British government

as an important determinant of its behavior, but the context in which it

operated also needs to be taken into account. The most important element of context seems to

me to the rivalry between European powers to obtain advantage in trade with India.

Portugal came

first.

Perhaps you

can recall from school history lessons that Vasco da Gama sailed to India around

the Cape of Good Hope in 1498. This was the culmination of voyages of discovery

by Portuguese sailors, including the important contribution of Bartolomeu Diaz,

who had rounded the Cape some years earlier.

The Portuguese government was heavily involved in this exploration, and in what followed. In his book, The Portuguese in India, M.N. Pearson relates how the king, D. Manuel, invited da Gama to command the expedition when the latter happened to wander through the council chamber where the king was reading documents.

After da

Gama’s voyage, the Portuguese court debated whether they should use force to

seek a monopoly in the Indian Ocean or be peaceful traders. They chose force.

Their aim was to try to monopolize the supply of spices to Europe and to

control and tax other Asian trade. There was, of course, a great deal of trade

in the Indian Ocean prior to Portuguese intervention, much of it controlled by

Muslims (from India as well as the Middle East).

The

Portuguese built forts in India to protect their trading activities. Some local

rulers saw advantage in giving the Portuguese permission to establish forts,

but they often used force. Goa was conquered in 1510. The Portuguese obtained permission

to build a fort at Diu in 1535 (and had ceded to them the islands that today

form Mumbai) because the sultan of Gujarat, Bahadur Shar, wanted Portuguese

help after being defeated by the Mughal emperor, Humayon. The Portuguese

obtained Daman from the sultan in 1559 and immediately began construction of

the fort at Moti Daman. Building of St Jerome fort (my photo below) commenced

in 1614, but was not completed until 1672.

The Dutch eclipsed the Portuguese early in the 17th century.

The

Portuguese were unable to prevent competition from the Dutch because the latter

were “better financed, better armed, and more numerous”. The Dutch blockaded

Goa from 1638 to 1644 and again from 1656 to 1663.

The Dutch

East India Company was founded by the Dutch government in 1602, not long after

the English formed the EIC. Both organisations were granted trade monopolies,

and combined private investment and the powers of the state in a similar manner.

In the early

18th century there was fierce rivalry between the Dutch and English over

the spice trade in Indonesia. That ended with the English quietly withdrawing

from most of their interests in Indonesia to focus elsewhere, including India.

The

transformation of British activities in India

In the 17th

century, the EIC established trading posts in Surat, Madras, Bombay and

Calcutta with permission from local authorities. The French India Company

offered increasing competition during the latter half of the 17th

century and into the 18th century.

The initial

objectives of both the EIC and the French were commercial, but their conflicts

in Europe spilled over into India. The British sought to fortify Fort William

in Calcutta against potential attack from the French. In 1756, the French encouraged

the nawab of Bengal to attack Fort William. After the fall of Fort William, the

surviving British soldiers and Indian sepoys were imprisoned overnight in a

dungeon where many died from suffocation and heat exhaustion. The prison became

known as the Black Hole of Calcutta. The number of fatalities is disputed, but

the incident seems to have provided impetus for the EIC to seek to wield

greater political power in India to protect its commercial interests.

My photo of

the Black Hole monument in the grounds of St John’s church in Kolkata.

EIC forces

led by Robert Clive (Clive of India) retook Calcutta in 1757 and went on to

defeat the nawab and his French supporters at Plassey. Clive’s victory was

aided by a secret agreement with Bengal aristocrats which resulted in a large

portion of the nawab's army being led away from the battlefield. The person

responsible for this treachery, Mir Jafar, was rewarded by being installed as nawab.

Clive rewarded himself and EIC forces from the Bengal Treasury.

A few years

later, as governor of Bengal, Clive arranged for the EIC to collect land tax revenues

in Bengal by appointing a deputy nawab for this purpose. The conquest of other

parts of India was planned and directed from Calcutta. Amartya Sen has noted:

“The profits

made by the East India Company from its economic operations in Bengal financed,

to a great extent, the wars that the British waged across India in the period

of their colonial expansion.”

Consequences

and responses

The worst

consequences of EIC rule became evident during the Bengal famine of 1770. The company

was apparently more concerned to maintain land tax revenue than to relieve to

the suffering of peasants. Its policies contributed

to the massive loss of life during the famine. Adam Smith presumably had that

in mind when he suggested in Wealth of Nations:

“No other

sovereigns ever were, or, from the nature of things, ever could be so perfectly

indifferent about the happiness or misery of their subjects, the improvement or

waste of their dominions, the glory or disgrace of their administration; as,

from irresistible moral causes, the greater part of the proprietors of such a

mercantile company are, and necessarily must be.” (V.i.e 26)

By reducing

the agricultural labor available to generate taxable income, the famine caused the

EIC to experience a subsequent loss of revenue. The British government provided

financial relief to the company but arranged to supervise it. Regulation of the

EIC was further increased in 1784, when British prime minister William

Pitt the Younger, legislated for joint government of British India by the EIC

and the government, with the government holding the ultimate authority.

The British

government seems to have been engaged in an ongoing balancing act to placate

both supporters of the EIC, including investors and former employees, and its

critics, including prominent individuals like Edmund Burke and Adam Smith.

Pitt’s India

Act stated that to pursue schemes of conquest and extension of dominion in

India are “measures repugnant to the wish, the honour and the policy of this

nation”. Perhaps that was an honest statement of the British government’s

policy objective, but it is doubtful that it had any impact on the extension of

British dominion in India.

Fortune

seekers

During the

18th century, India was seen as offering opportunities for young

British men to obtain a fortune, become well-connected, and to marry well.

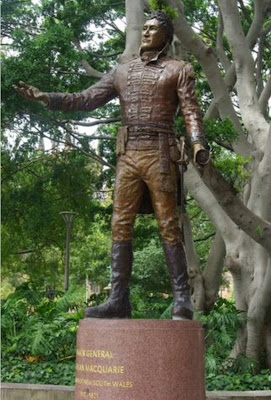

Lachlan

Macquarie, who (in

my opinion) ultimately become one of the best of Australia’s colonial

governors, expressed views, while a young army officer serving in India, that

may have been fairly typical.

In his biography of Macquarie, M. H. Ellis notes that in 1788 Pitt and his followers had cramped the style of young army officers in India by reducing their allowances. Macquarie recorded in his diary: “ … our golden dreams, and the flattering prospects we had formed to ourselves in Britain, of soon making our fortunes in the East, must now all vanish into smoke; and we must content ourselves, with merely being able to exist without running into debt” (p 18).

Macquarie’s

hopes for a change in fortune rested on being called to active service. He had

his wish during the third Anglo-Mysore war. The war ended after the

1792 Siege of Seringapatam led to the signing of a Treaty in which Tipu Sultan

surrendered half of his kingdom to the EIC and its allies. Macquarie noted

that news of the cessation of hostilities “damped the spirits of every one who

wished the downfall of the Tyrant and hoped to have the satisfaction in a few

days more, of storming his capital”. The storming of Tipu’s capital would presumably

have offered the prospect of looting, but Governor-General Cornwallis managed

to maintain the morale of his troops by announcing payment of a “handsome

gratuity in lieu of prize money”. (Ellis, p 39)

India’s

civil wars

Disunity

within India was another important element of the context in which the EIC

ended up ruling India. British colonial expansion occurred at a time when the

power of the Mughal empire was declining, with much of its territory falling

under the control of the Marathas. In the south of India, the rulers of Mysore

and Travancore were also powerful. The EIC sided with different rulers in

different locations at different times. For example, at the time of the Third

Anglo-Mysore War, referred to above, the Marathas were allies of the EIC. That

war occurred because Tipu, an ally of France, had invaded the nearby state

of Travancore, which was a British ally.

Why did

EIC rule end?

In 1813 the EIC

lost its monopoly over British trade with India. The opening of access to

competing traders seems to have been partly attributable to growth of the free

trade lobby in Britain.

In 1833, the

EIC was reduced to the status of a managing agency for the British government

of India. The government took over the company’s debts and obligations, which

were to be serviced and paid from tax revenue raised in India.

EIC rule of

India finally ended following the Indian Rebellion of 1857, which is now also referred to as

the First War of Independence. I took this photo at an Indian airport.

Colonial rule

was formally transferred to the Crown in the person of Queen Victoria in

1858. The British government took over the Indian possessions, administrative

powers and machinery, and the armed forces of the EIC.

In my view, EIC

rule ended because the company had a hopeless business model. The company was

obviously successful in conducting wars in India, and some employees of the

company made fortunes as a consequence. But the company’s attempts to service

debts incurred by imposing taxes on the people of India were inherently

problematic. Such taxes made it inevitable that the company would incur high

ongoing costs to put down rebellions. The EIC’s conquest of Bengal raised

expectations that colonial rule might be a profitable activity for the company,

but it became incapable of surviving without government financial backing only

a few years later.

Was a

better option possible?

John Stuart Mill - in his role as a spin doctor

employed by the EIC rather than an eminent philosopher - opened his last ditch defence

of the EIC by pointing out that at the same time as the company acquired a “magnificent

empire in the East” for Britain “a succession of administrations under the

control of Parliament were losing to the Crown of Great Britain another great

empire on the opposite side of the Atlantic”. (Mill is quoted more fully by

Richard Reeves in John Stuart Mill, Victorian Firebrand, p 258.)

Mill was obviously

attempting to present a persuasive case to British politicians at a time when

most of them perceived “empire” to be a desirable objective.

These days,

people who want to defend the empire-building activities of the EIC in India

are more likely to suggest that the institutional legacy of British rule,

including a united India (if you overlook the tragedy of partition) would

otherwise not have been possible. Amartya Sen has pointed

out the weakness of that argument:

“Certainly,

when Clive’s East India Company defeated the nawab of Bengal in 1757, there was

no single power ruling over all of India. Yet it is a great leap from the proximate

story of Britain imposing a single united regime on India (as did actually

occur) to the huge claim that only the British could have created a united

India out of a set of disparate states.

That way of

looking at Indian history would go firmly against the reality of the large

domestic empires that had characterised India throughout the millennia. …”

Summing

up

The East

India Company came to rule India as an unintended consequence of British

government intervention seeking trading advantages over other European powers.

This intervention occurred against the background of previous involvement in

Indian trade by Portuguese and Dutch governments, and in the context of intense

rivalry with the French government’s trading company.

The East

India Company’s schemes of conquest and dominion were made possible by disunity

within India, which provided it with opportunistic allies. However, the company’s

business model of taxing subjugated Indians was not capable of generating

sufficient revenue to service debts incurred in subjugating them and

maintaining order. Rather than let the company fail, the British government

became increasingly involved in directing its activities, and ultimately displaced

it.