Why should

you care about the economic opportunities available to the people of Papua New

Guinea? Perhaps some readers didn’t even

know the location of Papua New Guinea (PNG) before looking at the accompanying

map.

There is a

lot to be said for the view that the people of PNG should be left to solve

their own problems for themselves. However, one of the problems the people of

PNG need to solve is how to reduce their dependence on foreign aid. Another

problem they need to solve is how to cope with living in a part of the world in

which China and the United States are increasingly competing for influence.

Joe Biden,

the president of the United States is to visit Port Moresby, the capital of PNG, on May 22 for discussions with Pacific Island

Forum members, while on his way to Sydney for a Quad meeting.

My personal

interest in the economic opportunities available to people in PNG stems from

having worked there as a consultant on economic policy, having visited as a

tourist on several occasions, and not least, from having relatives who live

there. I maintain an interest in economic and social development in PNG and have

written about it on this blog in the past (here, here, here, and here).

In this

article I suggest that opportunities for human flourishing in PNG are less

promising than recent macroeconomic indicators might suggest. After considering

some macro-economic indicators, I briefly discuss population statistics, corruption

and profligacy, the law and order problem, poor opportunities for young people,

and lack of economic freedom.

Macro-economic

indicators

The World Bank’s latest

Economic Update paints a fairly rosy picture, with economic growth of 4.5 percent

for 2022. Government revenue from mining and petroleum taxes surged (reflecting

the impact of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on natural gas prices). The

increased revenue led to a reduction in the fiscal deficit. The magnitude of

public debt remains a problem, with interest payments exceeding public spending

on both health and education.

Inflation at around 6 percent per annum is not unduly high

by comparison with other countries, but rising food prices have made life

increasingly difficult for many people in urban areas. Foreign exchange

rationing, associated with pegging of the Kina against the USD, has been a

hindrance to business.

Population

statistics

I mention

population statistics mainly because questions that have recently been

raised about the

reliability of official estimates of the population illustrate the existence of

deep-seated problems in public administration. The official estimate of

population for 2022 is between 9 and 11 million. However, a leaked UN report

has suggested that the population could be as high as 17 million. In this

instance, the official estimate seems more likely to be correct. However, the

last credible census took place 20 years ago, so no-one really knows the size

of the PNG population.

It is widely

accepted that the population of PNG has been growing rapidly and that the

majority of people are relatively young, probably under 25 years old.

Corruption and profligacy

Corruption is still a major problem in PNG, although there seems

to have been some reduction over the last decade. Of the 180 countries included

in the Corruption

Perceptions Index, only 50 were rated as more corrupt than PNG in 2022.

Profligacy in spending of public money by some government

ministers is legendary. For example, in 2018, when PNG hosted the APEC summit,

Justin Tkatchenko attracted controversy by purchasing 40 custom-made Maserati

luxury cars. He claimed that they would sell like hot cakes after the event.

Unfortunately, that didn’t happen. More recently, the same minister again

attracted criticism for taking an overly large contingent of people with him,

at public expense, to the coronation of King Charles III. It was his

intemperate response, labelling critics as “primitive animals”, which eventually

led to his resignation

from the position of Foreign Minister.

The law-and-order problem

There has been a law-and-order problem is PNG for many

years. In 2015 I wrote:

“It is unsafe for tourists to walk around most parts of Port

Moresby alone except within the boundaries of major hotels, modern shopping

malls and other locations where security is provided. The same applies to local

residents. Tourists are more fortunate than most of the locals because they can

afford to be transported safely from one secure area to another.”

It is particularly unsafe for women and girls to be in

public places. A recent article on DEVPOLICYBLOG

by Sharon Banuk, a university student, describes the nature of the problem that

she has faced in staying safe.

PNG is ranked second, behind Venezuela, as the country with

the highest number

of reported crimes per 100,000 people. The ranking of PNG seems to have remained

the same since 2017, having risen from 16th place in 2015.

Poor economic opportunities for young people

The law-and-order problem has been linked to the increasing

problem of youth unemployment in

an article by Ms.

Julian Melpa for the National Research Institute. A

recent

study found 68 per cent of people aged between 14 to 35 in Port Moresby

were unemployed. Even people with tertiary qualifications often find it

difficult to obtain employment.

The difficulty of finding employment is illustrated the

accompanying photo of job seekers, published with a report in The

National newspaper on Feb 6, 2023. The crowd were competing for

a few advertised vacancies at a hotel in Port Moresby.

Lack of economic freedom

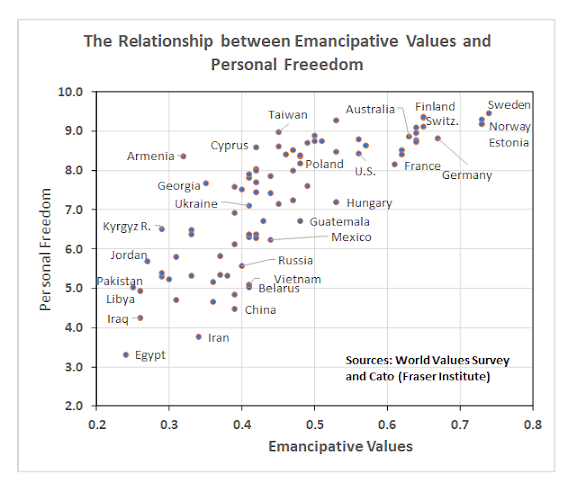

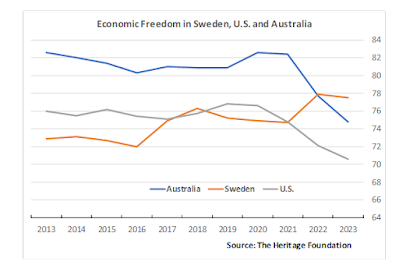

International agencies tend to label the main deficiencies in economic freedom in countries like PNG as governance problems. That

labelling may make their advice more palatable to politicians who have

ideological hangups about free markets but it obscures the adverse impact of

lack of economic freedom on incentives to invest, innovate and create greater

opportunities for human flourishing.

Only 36 of the 176 countries included in the Heritage

Foundation’s index of economic freedom have a lower ranking than PNG. A

similar picture emerges from the Fraser

Institute’s economic freedom ratings. Only 43 of the 165 countries included

in the Fraser index have a lower economic freedom rating than PNG.

PNG has particularly low ratings for rule of law (covering

property rights, judicial effectiveness, and government integrity) business

freedom, and investment freedom.

PNG governments have obviously been having major problems in

performing the core functions of government in protecting natural rights of

individuals to be safe and have opportunities to flourish. Governments face a

formidable challenge in protecting economic freedom in PNG, with most of the population

living in village communities and having little contact with the market economy.

However, similar challenges face governments in some other countries.

Some African countries which face similar challenges now seem to be performing

better than PNG in facilitating growth of economic opportunities.

PostscriptReaders who are interested in a more comprehensive picture of the well-being of people in PNG should visit the

relevant country site of The Legatum Prosperity Index. For the purpose of the Legatum index, prosperity is defined broadly as occurring "when all people have the opportunity to thrive by fulfilling their unique potential and playing their part in strengthening their communities and nations".

My article mentions a visit to PNG by Joe Biden, which was scheduled for May 22. Unfortunately, this visit will not occur as planned because he has given higher priority to political negotiations over the U.S. government debt ceiling.