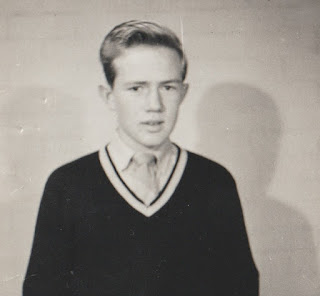

The kid in

the photo believed that the material world is an illusion. Those beliefs about

the nature of reality probably led him to be somewhat less materialistic than

he would otherwise have been. However, an observer would have had to look

closely to find any evidence that he, and his school colleagues who held

similar beliefs, were behaving as though they did not believe the account of

reality provided by their sense organs. They didn’t attempt to survive without

food, to defy gravity by jumping off tall buildings, or to do much else to

suggest that they had a different view of reality than most other teenagers

living in Australia in 1960. The main difference an astute observer would have

seen was their practice of treating illness as an error of thinking and viewing

medical intervention as unnecessary and undesirable under most circumstances.

I am

writing this article because a few people who have known me at different times

of my life might be interested to know something about the process by which my

beliefs have changed over the years.

Youthful

preoccupations

When I was a

child, I liked sitting on the gate post of a fence separating our garden from

the farmyard. That was my favorite spot for observing what the horses, sheep

dogs, cows, pet lambs, humans etc. were doing in the farmyard. One day when I

was sitting there – I would have been about 6 years old - my father told me

that everything I saw in the farmyard was an illusion. I thought at first that

he was joking, but he was in the process of informing me that he had decided to

attend the Christian Science church and had arranged for me to attend their Sunday

school.

Over

subsequent years, I gradually became immersed in the teachings of Mary Baker

Eddy, and her book, Science and Health (S&H). The final 3 years of my secondary

education were spent as a border at Huntingtower, a school run by Christian

Scientists in the Melbourne suburb of Mount Waverley. At that time, the school

only accepted students who had a family background in Christian Science.

Huntingtower still has a focus on the individual personal development of

students and provides excellent educational opportunities. I am grateful that

one of my aunts paid the fees to enable me to attend that school.

I have long

been aware that there was some similarity between Mrs. Eddy’s teachings and the

philosophy of Plato. I now see a closer resemblance to the Neoplatonism of

Plotinus. Plotinus believed that “The One”, the absolutely simple

first principle of all, was the cause of being for everything else in the

universe. Mrs.

Eddy wrote:

“Principle and its idea is one, and this one is God, omnipotent,

omniscient, and omnipresent Being, and His reflection is man and the universe”

(S&H, 465-6).

The

Neoplatonists saw life’s purpose as being “to bring back the god

in us to the divine in the All”. Mrs. Eddy urged her followers:

“We must

form perfect models in thought and look at them continually, or we shall never

carve them out in grand and noble lives. Let unselfishness, goodness,

mercy, justice, health, holiness, love — the kingdom of heaven — reign within

us, and sin, disease, and death will diminish until they finally disappear”

(S&H, 248).

Secular

pursuits

I abandoned

Neoplatonism at the end of my teen years. At that time, I didn’t consciously

reject that belief system even though I can remember becoming increasingly

frustrated at the difficulty of attempting to follow Mrs. Eddy’s injunction:

“Stand porter at the door of thought” (S&H, 392). My social life and

academic interests made me less inclined to spend time engaging in what I was

coming to view as speculations about the nature of “ultimate reality”. I was beginning to study economics, so my

thinking focused increasingly on how human aspirations could best be met. At

that time, I became interested in the writings of J S Mill on liberty and

utilitarianism.

Over the years, my philosophic interests developed along

with a work career focused on public policy relating to economic development,

international trade, productivity growth and technological progress. That led

to increasing interest in the role of liberty in economic progress, and human

flourishing more generally.

As a consequence of my interest in human flourishing, I have

come to view Aristotle as the greatest of the philosophers of Ancient Greece. My

book, Freedom,

Progress, and Human Flourishing, explains the framework of my current thinking.

These days, the idea that the evidence of our senses is

illusory seems as strange to me as it was when I was the child sitting on the

gate post. Our senses provide the direct experience of reality that members of our

species require to thrive. Since we are conscious beings, we are aware of our own

use of maps, and models (both metaphorical and actual) to communicate and reason

about what we experience. However, we also know that maps and models do not always

correspond to reality. The search for truth is about seeking better maps and

models.

The

lurking questions

There were two questions lurking in the back of my mind after

I had abandoned Neoplatonism. First, how could a change in thinking bring about

the healing of serious illnesses which seemed to have a physical cause? Second,

why did the same techniques sometimes fail to provide the lasting healings

hoped for in respect of disorders that seemed to have a psychological rather

than physical cause?

I do not doubt the veracity of most of the large number of

testimonials that church members presented about healings that they experienced.

As I remember it, most of the church members I knew either had personal

experience of healings themselves or were family members of people who had

obtained healings. The prevalence of healings seems to me to be the most

obvious factor explaining the rapid growth of this church in the first half of

the 20th century, when medical science was less advanced than it is today.

Advances in medicine provide the most obvious explanation for the decline in church

membership in recent decades.

I think the answer to my first question lies in the

potential impact of a change of an individual’s thinking on their body’s

natural defences against disease. For example, a substantial amount of evidence has

accumulated about the relationship between psychological stress and the human

immune system. There is a lot of advice available about the importance of

stress management in maintaining good health, and about how to manage stress

via physical exercise, breathing exercises, yoga, meditation, and so forth. However,

I don’t think many people give enough attention to the potential for negative thinking

associated with medication to influence its efficacy. Before you decide to take

any medication prescribed to you, it seems to me to be wise to have at least a

rudimentary knowledge of how the medication works and the impacts that most

users experience. If that doesn’t provide a basis for you to expect positive

outcomes, perhaps you should seek another opinion.

My answer to the question of why lasting healings didn’t

always occur in respect of psychological disorders is that an appropriate

change of thinking had not actually occurred. That was not necessarily attributable

to insufficient vigilance as “porter at the door of thought”. In my own

experience, I think the opposite was the case. Trying hard to keep fear of

stuttering and blocking out of my mind resulted in greater fear of disfluency

than I would otherwise have experienced. The reason for that became clear when someone

suggested that I try the “don’t

think of a pink elephant” exercise. The exercise consists of trying very

hard not to think about pink elephants and then observing what images come to

mind. Deliberate attempts to suppress thoughts makes them more likely to occupy

your mind.

The questions lurking in the back of my mind made me

receptive to Neuro-Semantics – a model of how we create and embody meaning

developed by Michael Hall and Bobby Bodenhamer - when I learned about it 20

years ago. For present purposes, I think the message of Neuro-Semantics can

best be illustrated by the following

quote from an article by Michael Hall entitled, “The Inner Game

of Frame”:

‘The frames we set about our experiences are much, much,

much more important and critical than our experiences. In this, “there is

no good or bad but thinking makes it so” as Shakespeare noted. In this,

“men are not disturbed by things, they are disturbed by their interpretation of

things.” In this, “as we think in our heart, so we are.” In this we

have the cognitive-behavioral foundation for human functioning.’

Readers of my book, Freedom,

Progress, and Human Flourishing, will find a reference to Hall’s views

on the importance of frames of meaning in the discussion of why people do not

always move on to satisfying higher needs, as Abraham Maslow suggested they

would, once their basic needs have been met (p 168-9).

Beyond utilitarianism

One aspect of Mrs. Eddy’s teachings that I have held on to

is the idea that the identity of the individual person is a metaphysical

concept. Mrs. Eddy made the point persuasively as follows:

‘If the real man is in the material body, you take away a

portion of the man when you amputate a limb; the surgeon destroys manhood, and

worms annihilate it. But the loss of a limb or injury to a tissue is

sometimes the quickener of manliness; and the unfortunate cripple may present

more nobility than the statuesque athlete, — teaching us by his very

deprivations, that “a man’s a man, for a’ that.” ‘ (S&H, 172)

The Neoplatonism of my youth has also left me receptive to

the idea that to fully flourish we need to be willing to transcend utilitarian

preoccupations. That idea is, of course, also present in Aristotle’s view that

practice of the virtues is central to individual flourishing. In Freedom,

Progress, and Human Flourishing, I summarised my current view as follows:

“Liberty

and technological progress give us potential to obtain more of the basic goods

of flourishing humans. To fully flourish, however, we need to be willing to

transcend utilitarian preoccupations and to contemplate what our human nature

requires of us as individuals. Perhaps it is in our nature to bring wonder into

our lives by seeking the essence of truth, beauty, and goodness. If so, we may

take pleasure in doing that, whilst rejecting the idea that it is appropriate

to employ the metrics of pleasure and pain to assess the worth of our endeavors”

(197).

Postscript

I neglected to mention my guru, Tim Gallwey. I have been a fan of Tim Gallwey's books for more than 20 years. I found "The Inner Game of Golf" particularly helpful in aspects of my life that have little to do with golf. Tim Gallwey's insights about the inner game of golf helped me to see some personal problems in perspective. (By the way, I play golf about once a year and play no better might be expected!)

Tim Gallwey describes how people tend to interfere with their performance in activities requiring muscle coordination when they respond to self-doubt by "trying harder". Trying harder often entails increasing muscle tension. Gallwey's books offer practical suggestions to circumvent self-doubt.

Tim Gallwey says: “We all have inner resources beyond what we realize”. You discover your true identity as you draw on those resource to master the inner game.

In this video Tim Gallwey talks about the personal philosophy that motivates him.

My podcast episode entitled, "Tim Gallwey, my Inner Game guru", can be found here.