Lachlan Macquarie was governor of New South Wales from 1810

to 1821. At that time, the colony comprised much of the Australian mainland

(known then as New Holland), Tasmania (Van Diemen’s Land) and other island

territories.

Many years ago, when I studied Australian history at school,

I came to the view that Macquarie, the fifth governor of New South Wales, was

one of the best of the colonial governors. I still feel that Macquarie made a positive contribution to cultural values that are

widely held in Australia today. It is unusual for despots to be good people, but I think Macquarie was one.

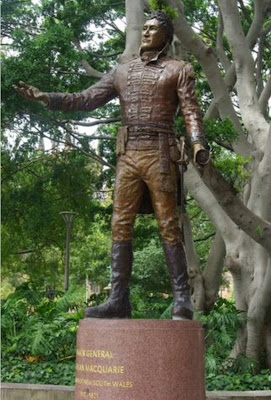

The above photo is of a sculpture of Lachlan

Macquarie, located by Macquarie Street in Sydney. The inscription on the plaque

describes Macquarie as “a perfect gentleman”, while that on his tomb in

Scotland describes him as “The Father of Australia”.

Macquarie is also remembered in the many places named after

him. Some that readily come to mind are the suburb of Canberra, where my family

lived for several years; Port Macquarie, on the north coast of New South Wales,

where we have enjoyed some holidays; and Lake Macquarie, where we now live.

Proposal to re-name Lake Macquarie

I have been prompted to write this article because there is currently a move for Lake Macquarie to revert to its original name, Awaba. The Indigenous inhabits of the region, Awabakal people, knew the lake by that name for many thousands of years prior to European settlement. I see no reason to oppose the name change if it can be accomplished without a great deal of cost and confusion, and in a spirit of reconciliation.

However, some of the proponents of the name change seem to

me to be making it difficult for it to be accomplished in a spirit of

reconciliation because they are arguing that Lachlan Macquarie does not

deserve to be honoured. It looks to me as though they want him to be cancelled!

Those who seek to denigrate Macquarie refer to the fact that

he ordered a military operation that led to a massacre of aboriginal people. They

don’t have regard to the circumstances in which that order was given, or

consider what alternative courses of action Macquarie could have taken.

What would you have done in his shoes?

I can understand why some readers might object to the idea

of contemplating what it might be like to occupy the shoes of a colonial

despot. Some might argue that those shoes did not have to be filled. The

British could have chosen not to establish the colony in the first place. They

could have found some other way to solve their problem of over-crowded prisons,

and thus avoided encroaching upon the lands of Indigenous people.

However, as I see it, if similar choices to those

confronting Macquarie were not faced by an alternative British despot, they

would have been faced by a despot from France or some other European country.

When Britain established the colony, other European powers were seeking to

establish colonies throughout the world. So, if the British had not established

the colony, it is highly unlikely that the Indigenous people would have been

left alone to pursue their traditional lifestyles.

Lachlan Macquarie was a reluctant appointee to the position of governor. The biographical history by M H Ellis indicates that after having served with the British army in India for 25 years, Macquarie considered it to be unfair that he was being posted to the colony. (Ellis, 166)

In contemplating what you would have done in Macquarie’s

shoes, it might be helpful to consider his motives, the circumstances that led

to the military operation, and whether alternative approaches might have led to

more tranquil relations between Indigenous people and settlers.

Macquarie’s motives

On arrival in the colony, Macquarie expressed the wish that

“the natives of the country, when they came in the way in a peaceable manner,

might not be molested in their persons and property by anyone, but that they

should always be treated with kindness and attention, so as to conciliate them

as much as possible to the British Government and manners.” (Ellis, 179)

How could Macquarie expect the Indigenous people to remain

peaceable when their land was being taken away from them? I see some evidence

that Macquarie saw potential for mutual benefit from more productive use of the

land, and by helping Indigenous people to develop new skills and habits. From

his paternalistic perspective, the Indigenous people were wasting their lives

“in wandering thro’ their native woods … in quest of the immediate means of

subsistence”. He saw them as having qualities that “if properly cultivated and

encouraged might render them not only less wretched and destitute” but

“progressively useful to the country according to their capabilities”. He

expressed the view that they could “advance toward a state of comfort and

security”. (Ellis, 352-3).

Macquarie allocated some land for use by Indigenous people

on the grounds that they were “a harmless race, who have been without struggle

driven by the progress of British industry from their ancient places of

habitation”. (Ellis, 358)

Unfortunately, Macquarie received only lukewarm support for

this approach from the British government. If the policy had been pursued

vigorously by the British government, the Indigenous people would not have

suffered such great deprivation and humiliation in subsequent decades.

Circumstances that led to the massacre

A deterioration in relations between Indigenous people and

European settlers seems to have occurred in 1814 mainly because the settlers

retaliated when Indigenous people helped themselves to unfenced fields of corn

planted by the settlers. Macquarie saw fault on both sides. As he saw it, there

had been a violation of property rights by the Indigenous people, but it was

not a serious violation. He admonished the settlers to behave with patience and

forbearance and not to take the law into their own hands. He warned that future

aggressiveness by either whites or blacks would be punished in an exemplary

manner. (Ellis, 353-4)

Nevertheless, attacks on settlers continued and some

abandoned their farms. The governor felt that a severe response was required to

prevent the frequent occurrence of trouble. In April 1816 he ordered a military

action to drive the mountain tribes a safe distance from the settlement. (Ellis, 355-6) Those seeking an account of the

massacre can find relevant documents on the Australian

Museum website. In a subsequent proclamation, Macquarie gave settlers the

right to drive away Indigenous people who appeared armed with weapons within a

mile of any town, village, or farm.

The military action had the desired effect of restoring

order. Members of local tribes attended a friendly meeting which the governor held

in December 1816 to, among other things, consult with them “on the best means of

improving their present condition”.

Alternative approaches

The limits of my knowledge of the relevant history make it

difficult for me to assess the options that faced Macquarie. Perhaps there was

potential for him to restore order by adopting a response that was targeted to

a greater extent at individual perpetrators of violence rather than on tribes

of people, but I have not seen any authoritative discussion of that possibility.

It seems unlikely that Macquarie would have considered the

option of attempting to achieve peace by limiting the area of European settlement.

That approach would have been likely to lead to rebellion by the settlers and Macquarie’s

replacement as governor.

The governor could have continued to pursue a conciliatory

approach but there is no reason to believe that would have been successful in

discouraging attacks on settlers, or setter retaliation. The most likely

outcome, it seems to me, would have been an increase in violence on both sides,

with a more extensive military intervention required eventually to end the

conflict.

Concluding comments

My view that Lachlan Macquarie made a positive contribution

to cultural values that are widely held in Australia today is based mainly on the

humane approach he adopted toward the people of the colony. He has been

remembered particularly for his humane treatment of convicts and ex-convicts,

who made up about 90 percent of the European population of the colony at the

time of his appointment. Macquarie saw that some of the most meritorious people

in the colony had come there as convicts and sought to treat them justly by

giving them the opportunities to hold responsible positions.

Macquarie sought to extend this humane approach to the

indigenous people, but was faced with difficult choices. Those who criticize

the choices he made should consider what they would have done in his shoes.